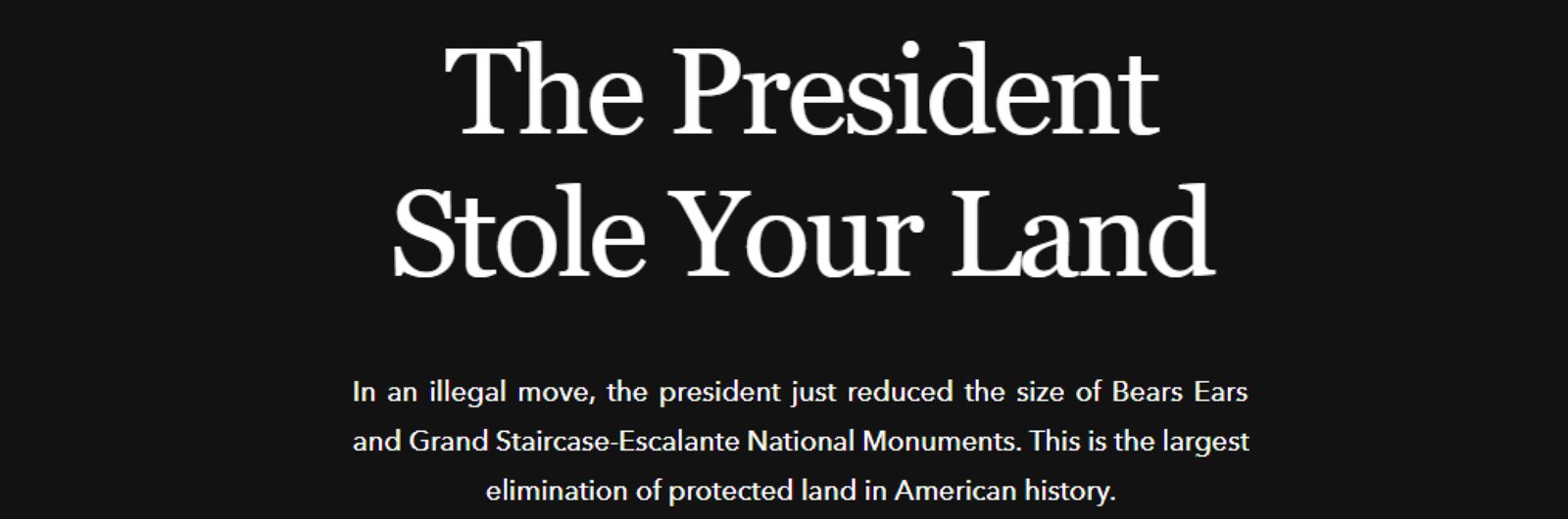

On December 4th, people who visited the homepage for Patagonia, the popular California-based clothing company known for its fashionable outerwear, were greeted not with a giant idyllic photo of ski slopes or mountain ranges overlaid with the familiar top-navigation headers of the modern webshop, but instead with a simple black background and this statement, in large font: The President Stole Your Land.

Scrolling down the page, visitors learned the meaning behind those words. The Trump administration had just that day announced a rollback of federal protections on the Bears Ears and Grand Staircase-Escalante national monuments in Utah—a combined two million acres worth of land. According to Patagonia, via a study by the Center for Western Priorities, this represented the largest elimination of protected land in American history. As a means of protest, Patagonia announced plans to sue the administration to prevent the national monuments from losing their protections, which would leave lands of cultural and archeological import to Native Americans vulnerable to any number of corporate interests, like coal and uranium mining, logging and oil extraction.

The makeover of Patagonia’s homepage immediately went viral, trending on Twitter and Facebook, at least amongst well-to-do liberals—i.e. the type of educated, upper-middle-class, environmentally-conscious people who would buy Patagonia products in the first place. It was a crafty piece of branding. While ostensibly sacrificing sales in the short-run on its webshop—through the deterrence or obstacle of the temporary homepage—it boosted its public visibility amongst its target demographics, thus (likely) increasing sales in the long-run—either by attracting new customers or strengthening the loyalty of existing ones. And yet it succeeded precisely because it was not a piece of branding at all; it was a genuine protest. One need only look at Patagonia’s history of social responsibility—keeping close tabs on their supply chain to make sure everyone’s making a living wage, for example—and environmental activism—the development of Worn Wear, essentially a second-hand shop that exclusively stocks old Patagonia clothing, and their numerous environmental grants, to name just a few—to grasp the sincerity of their motives. That they stand to profit from this latest political initiative—or Worn Wear, for that matter—does not obviate the goodness of the act. In fact, they would have you believe that the more money they make the more they can get done for their various causes. And there’s no reason, as far as I can tell, why we shouldn’t believe that to be the case.

Corporations, of course, have a long history of activism, with varying levels of success and sincerity. But few* have pulled it off with such panache as Patagonia, because Patagonia, beyond being a brand, has a personality. I don’t mean personality in the Business 101 sense of the word; what I mean is that it seems like there is an actual person behind their actions. When the phrase “The President Stole Your Land” blazed across the homepage of Patagonia, it not only communicated the ethos of Patagonia’s brand, but called to mind, for me at least, the real people making the decision to put that up. In a corporate world that so often expresses itself through simulacra of expression—an executive’s edited iteration of a copywriter’s glossy interpretation of real talk—Patagonia’s message felt intrinsically human. “The President Stole Your Land” was powerful because it subliminally meant: “The President Stole Our Land. And We Want You to Help.”

Just the other week, UrbanDaddy’s own Kady Ruth Ashcraft wrote a screed against sassy corporate Twitter accounts, citing Wendy’s recent beef with McDonald’s, Netflix’s consistently sardonic and self-aware badinage and MoonPie’s ridiculous back-and-forth with someone named Kaela Thompson, who lived to rue the day she made her disdain for MoonPie’s public. Anyone following popular humor Instagram accounts like Fuck Jerry would recognize one or more of these Tweets. They were quickly and effectively plucked from the corporate underworld of Twitter—who really follows MoonPies, anyway, and why?—and meme-ified for broader consumption. Some have called for Netflix’s social media editor to get a raise; others, like me, have probably felt more goodwill towards Wendy’s since the time they got stoned and dipped their fries in a chocolate Frosty.

Ashcraft suggested that while it’s understandable why companies would do this—to be hip and personable—it’s still possible, in a moment when public decorum has devolved to meet the standards of our first Twitter president, to be hip and personable sans snark. Though we can acknowledge the effectiveness of the branding technique, it doesn’t change the fact that these corporations are just trying to sell us more shit—oftentimes, shit like Wendy’s that we don’t even want (unless we’re stoned).

I happen to disagree with her. Twitter is almost all snark. An informal study recently conducted by me suggests that approximately 94% of Twitter is snark, and 6% of Twitter is commentary on how terrible Twitter is—mostly because of the snark. Meeting us on that level, on this platform, is not only good branding: it is, as with Patagonia, a reminder that behind Wendy’s cold cartoon eyes and Netflix’s giant shadowy “N” there exists a real person with a human brain who likes to compose snide Tweets just like the rest of us. Certainly, a corporation that attempts to “be your friend”—as they have since the beginning of time—in order to sell you something is disingenuous; and yet it feels even more disingenuous to regurgitate lifeless corporate-speak on a medium so inherently personal—and personality-driven. What Netflix, and Wendy’s to some extent, have realized is that, in today’s day and age, it’s perhaps more authentic to recognize the slick artifice of your own corporation-qua-corporation—by posting Tweets from a person with a legitimate point-of-view—than to stick with a lobotomized message everyone knows is bullshit, anyway.

This recognition of artifice is a hallmark, naturally, of postmodern advertising on other platforms—TV, print, radio, etc. Yet the most salient example beyond Twitter may lie in podcast ad reads, some of the best of which, in my opinion, routinely break out of the bit. Any listener of Crooked Media’s popular Pod Save America podcast knows that its three primary hosts—Jon Favreau, Tommy Vietor and Jon Lovett—can barely get through an advertisement without laughing. As on the pod itself, Favreau often takes the lead, with Vietor as the straight man and Lovett as the jokester. Many of the ad reads, then, consist of Favreau and Vietor attempting to get through the script while Lovett badgers them with jokes and irreverent comments. It’s smart, though, both for the hosts and the product they’re advertising; by acknowledging the constriction of the form, they can circumvent its mundaneness—and make the ads both entertaining and on-brand.

None of this artistic subterfuge should distract from the fact that the point of branding and advertising is to sell us stuff. If anything, our awareness of these methods should have us putting our guards up even more than before. It’s one thing for Patagonia, or Netflix, or even Wendy’s to try to curry favor through a little personality; it’s quite another for the most prominent tweeter—and brand—in the country to do so. Because, of course, Donald Trump has harnessed this power—a lifting of the corporate or political veil—more effectively than any person or product. Say what you want about his tweets: unlike almost every other politician, they’re never not his. They have his personality—as awful as it is—written all over them.

*The “card game” company, Cards Against Humanity, is one of those few. It is almost all branding—all personality. Their ongoing campaign, Cards Against Humanity Saves America, is as effective a piece of activism and branding as Patagonia’s.