One male UrbanDaddy writer, Sam Eichner, and one female UrbanDaddy writer, Bailey Edwards, had a frank conversation about sexual assault and harassment and how best to be a male ally in the wake of recent events. This is an edited version of that conversation.

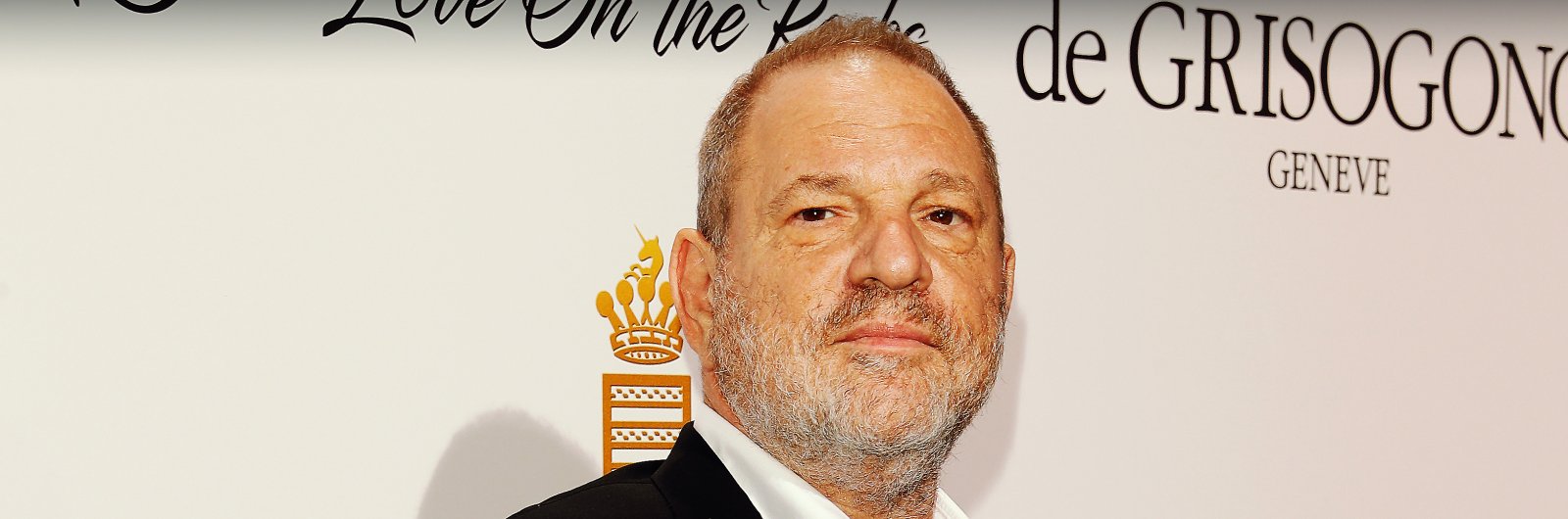

Sam Eichner: I recall mentioning to you while you were writing another article that when the Harvey Weinstein allegations and reports first started surfacing last week—they've continued to flow in this week, almost metronomically, at a nightmarish pace—it seemed to me "unsurprisingly surreal." How could Weinstein have sexually assaulted (or, in some alleged cases, raped) all these women for all these years without suffering any repercussions?

This was a question I asked myself instinctively, despite knowing full well the inanity of its premise. And yet I found myself wondering the same thing in the wake of the #metoo posts filling up my social feeds over the past few days. Intellectually, I'm aware of the pervasiveness of sexual assault/harassment; emotionally, though, I was still unprepared for it. For each "me too" I saw, my initial reaction, I'm afraid to admit, was a decidedly un-woke rhetorical: "You, too?"

I don't think I was alone in feeling this way. I imagine it's felt most profoundly amongst men like myself who would deign to consider themselves allies or even feminists (and not just in the "I'll grind on you vs you grind on me at a club" type of enlightened frat boy way). There's a difference between knowing sexual assault and harassment exists on the scale that it does and living that reality. Sexual harassment, micro or macro, unintended or grossly deliberate, is not something I think about, am conscious of or am forced to deal with on a daily (hourly, minute-ly) basis, the way women must. Men, myself included, often fail, if not to recognize, than fully realize that distinction.

I guess my reiterating this is a roundabout way of saying these recent events have forced some real introspection—about the way I've treated women and the way women I care about have been treated. Just the other day, my mom shared with me a story about being molested by a male instructor at a horse-riding camp when she was in second grade, and how, when her mom (my grandmother) called the camp to complain, they believed the instructor, not my mother. I'd never heard this story before. And it struck me that there are probably thousands upon millions of sons who've never heard their mothers' stories of sexual assault before, thousands upon millions of boyfriends who've never heard their girlfriend's stories before, thousands upon millions of friends—male or not—who hadn't heard their friends'—female or not—stories before. And I thought that if nothing else the fact that my mother felt comfortable enough—or felt it necessary enough, in our political climate—to tell me this held a quiet power. I can't help but think that if every mother who'd experienced sexual assault or harassment shared that experience with her son(s), the world might be a better place for women.

I don't think listening is enough when it comes to be a strong male ally, though, is it?

Bailey Edwards: I don't think listening is enough, sadly. It would be nice though, right?

In the wake of Harvey Weinstein, and the flood of #metoos, I wish I could sit here and tell you that I, too, was remotely surprised. I wish "You, too?" was my reaction. But instead, it's an unwavering "of course, you too...and you, and you," and on and on until my finger got tired of scrolling and my heart too heavy to see anymore before bed. It would surprise me if a woman in my life told me that they'd gone their entire life without being sexually assaulted or harassed. I'd ask how the weather was beneath the rock they'd lived under their whole lives.

I joke because I have to. Because the reality of being a woman is scary and unsafe, but it's a reality women are accustomed to. It's not shocking because it's not new for any of us. Nothing about the allegations against Harvey Weinstein, or the subsequent cover-up by his peers, have been shocking to women. It's shocking that it's finally toppling him. It's shocking that it finally matters enough to end a powerful man's career.

I've thought a lot about #metoo. How empowering it is to be able to speak up and see other women come together and have each other's backs. But I know a lot of women in my life who found it to be deeply triggering as well. Feeling pressure to own what happened to them or somehow they're not being strong, or to have to define themselves, even for a moment, by what men have done to them, can feel like another kind of violation. To once again handle the emotional burden of explaining to men that yes, of course, they'd been survivors of assault. How do you not know? How is this such a deep part of our reality and none of you have been paying attention? When you hear statistics that one in three women are victims of sexual assault, who do you think those women are?

They're us. And the trauma of each of our stories varies, but it's all of us. And to be a good male ally, men have to start recognizing that while it might be a painful realization, we need men to get there and it needs to not be on us to prove it to you. We shouldn't have to write #metoo for you to know what kind of world we live in. But since we have to, listen and be humbled by our stories. And don't get me wrong—I am so grateful we're having these conversations and that maybe this is a tipping point for us all. But Harvey Weinstein wasn't the first and he is certainly not the last. We didn't kill the beast and end sexual violence against women forever. There are so many more and they're all around us.

So what do we do now? How do we arm ourselves against current and future scenarios like this? Well, for one, don't just listen to women - support them and empathize with them. Be a part of their pain. Their pain is likely a source of conditions that you, the man, are also living in tandem with. You don't have to fix it for them, but you can be a part of the emotional labor that women have to take on to navigate these situations. This goes for a multitude of situations—if a woman tells you she was assaulted, don't just believe her—empathize with her. Go to her on an intellectual and emotional level. I recently recalled a situation at work to some coworkers about a former executive who had sexually harassed me over our chat at work. He's long gone, and I never reported it in part because I was young and scared of my job being in jeopardy. One of the men I relayed this on to said, "oh, okay," clearly uncomfortable with the situation. When I recalled the same story to my female colleagues I was met with variations on, "oof, gross. I'm so sorry that happened to you." Now, it's my opinion that the man I told that story in no way condones that behavior, but was unsure of what to say or do—so he did nothing. Experience and share in that violation. That is your place of work, too. That kind of thing should feel like a violation for you as well if it's going on in your space. Make women aware that they're not alone in those situations. If you know you're the kind of guy who would call the cops if you saw a rape in progress, that isn't enough. Silence is one of many ways of condoning behavior.

Reflect on the way you think about women. If all of this is only shocking because it's people near and dear to you that you didn't realize are survivors, that's something to unpack. Don't be Matt Damon! Don't be upset about what's happening because you "[have] daughters." This should all be upsetting because these are human beings we're talking about. Be introspective about why it's shocking to you that all of these women wrote "me too." If you know the statistics, but seeing that it was happening in your world was shocking, be brave and analyze that. It means you were okay knowing it was going on, so long as it didn't touch your world.

Be aware of how women are judged differently than men. And I don't just mean their appearances. Start observing how women at work are being perceived versus how men are. Do they get reprimanded for expressing disdain about a professional situation where a man is celebrated for his "passion for the project?" Are women getting interrupted at an alarming rate in meetings or being talked over? These may seem like small things, but these are the types of situations that lead to a culture of inequality. This is how the Harvey Weinsteins of the world get to flourish professionally for 30 years without consequence. Because if we don't treat women with the respect they deserve even on a basic level, I'm not sure why we expect that to extend to sexual violence. Sexual violence has never been about sex. Sexual violence has and will always be a form of power. Rape is the escalation of that. If we're not cognizant and diligent about evening out that abuse on a molecular level in our day to day lives, it will, without a doubt, extend to how we handle bigger and more traumatic forms of abuse.

And a good male ally will be up to the challenge, even when it feels inconvenient or difficult. After all, we do it everyday.

SE: I guess my big question here comes down to action. A lot has been made about the silence surrounding Weinstein's open secret of sexual assault, and many have called out the men who worked with Weinstein over the years and did or said nothing as being a part of the problem. I understand why a culture of silence surrounding sexual assault is problematic. That's why we're having this conversation in the first place. But at the same time, I feel like speaking out on a survivor's behalf can be a tricky business. These are not our stories to tell. And there are many women, at least one of whom I've dated in the past, who would say that these are not our battles to fight; that they wouldn't want us to "cause a scene" or "make it a big deal," either because they want to handle it on their own or because in so doing they might sacrifice other things (in the case of Weinstein's victims, their careers). It seems to me that the only way to solve this cultural problem is on an individual level, with men being willing and able to offer support and empathy, and most importantly, to believe the stories the women they care about tell them—to be there to help women decide what best to do for themselves. What do you think? How should a man navigate not staying silent without overstepping?

BE: You bring up a good point. Women don't need rescuing, but more importantly, each woman is going to have a varying opinion on how they want their experiences to be handled, so I'm not going to pretend to speak for all. But to answer your question more succinctly—yes. Yes, solving this problem culturally, or getting closer to it, will come down to the work we do on the individual level. Both in terms of listening, believing, doing the emotional work to understand women's experiences, but also in terms of listening to the women in your life about how they want you involved, if at all.

What I will say is that anytime I've been in a work meeting and a man has said, "Bailey was talking. Let her finish," I've never been angry. I've felt heard. That's not a weakness on my behalf, that's another human being recognizing that I was interrupted and it was frankly unprofessional. I've never felt angry when a man has responded to my recounting of harassment with empathy. The action here is not always very glamourous. It's not always going to be saving a woman in a bar from a big scary man who is physically endangering her. This action is unsexy, can feel small and is emotionally taxing. It's asking men to be on alert as if they were a woman themselves. It doesn't mean you have to live your life as a crusade, but it does mean you should aim to take note of it and let it affect you. And if you're unclear if a woman "needs your help", ask. If you saw a woman being put in a situation that you feel is unfair or dangerous, reach out to her and make it clear you're not being creepy (important), but that you want her to know you’re there and want to make yourself available (non-creepily), if she ever needs it. You'd be surprised how rarely that happens and how far it can go.

The big action, in my opinion, is going to come down to the emotional labor and introspection needed from men. The really unsexy, difficult shit that women have been working through in therapy for the better half of their lives. To analyze some of their own socialization and ask themselves if they can do better—from not staying silent, to questioning if some of their own behavior is problematic. Gloria Steinem has that quote about how we have begun raising our daughters like little boys, but the real change (which has yet to happen) is when we start to raise our boys like little girls. The kind of change we need is dependent on encouraging and fostering emotional intelligence in men and regarding said intelligence on the same level that we value other "manly" attributes.

SE: Amen. I think a lot of guys' first response to that suggestion would be to go on the defensive, as in: "oh, I'm not a bad guy, I didn't sexually harass anyone" or "don't blame me, I didn't come on to a 17-year-old Kate Beckinsale." Hell, I think that would've been my gut response just a few years ago. But defensiveness is the wrong approach, because it's not really about us. It's not about our pain. I'm piggybacking off this fantastic, eye-opening essay about intersectionality in film criticism when I say that when ostensibly well-intentioned, "good" men respond defensively towards women's suggestion that they could be doing more, they're derailing the conversation, and therefore progress. (Taken to the extreme—or, well, the alt-right—the notion that the oppressor is actually the oppressed is more or less the seed from which the yucky khaki-colored fruit of Trump-era white supremacy sprouts.) As a male friend of mine pointed out to me the other day, men who should be allies—men who consider themselves woke or progressive—can be the biggest problem, because they already see themselves as part of the solution. They don't necessarily think they need to do the work. But they—we, I—do. And while I think of myself as a good person, I'm not afraid to admit that there have been instances in the past, with regards to women, that I'm definitely not proud of. Ultimately, if we supposedly "good" men can't be really, truly good—introspective and analytical and emotionally intelligent, like you said—then what hope is there for the hordes of "bad" men out there (and in the White House), and the women they prey on?

BE: Bingo. Bingo. Bingo. Exactly. Men who are "good" are dangerous because they're sins aren't illegal, culturally frowned upon or as tangible as really bad men who go around raping and assaulting. It's a quiet danger of disbelief, doubt or inaction. Too lazy or self-centered to be bothered with the plight, but that's okay because they've never assaulted anyone themselves so they can sleep fine enough at night. But as a friend of mine recently said—having her male friends doubt her assault felt like being assaulted all over again.

Which brings me to my final point. Henceforth, UrbanDaddy will be called UrbanBoy until all men are grown as hell and we don't have to have these conversations anymore. I'm going to head to the bar where I'll watch my drink like a hawk because that's the reality of being a young woman in New York City, baby!