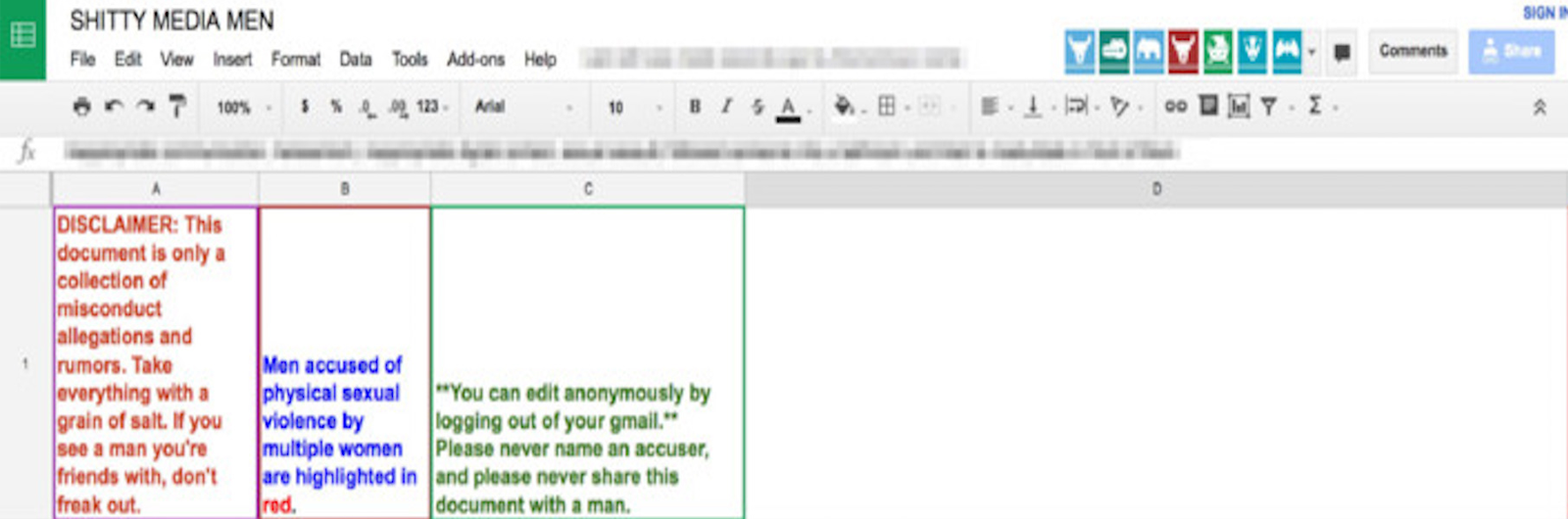

I recently wrote about the bravery of Moira Donegan, the woman responsible for creating the now-infamous Shitty Media Men list, a spreadsheet which acted as a physical "whisper network" for women in media to warn each other about predatory (or potentially predatory) men in the industry. It wasn't a particularly radical stance, but not everyone I know agreed with my choice to defend her. Not everyone felt her intentions were altruistic, or even if they did, they didn't agree with her choice to put into writing the quiet whispers of working media women. But I felt it was important to discern between her choice to create the list, and her lack of control in having it go public.

Some background: Donegan was essentially forced to out herself as the creator of the list when it was rumored that Harper's writer Katie Roiphe was preparing a piece to do exactly that. Roiphe's side of the story appeared on Harper's website this weekend, buried beneath Super Bowl coverage, under the headline “The Other Whisper Network.” My initial reaction to this piece was a tired groan. I wanted to give her a chance, I wanted to try and understand where she’s coming from and try to understand why she might think it's a good idea to out a woman trying to protect other women—tarnishing her name, at the very least, and putting her in serious danger, at the very worst. Roiphe's piece didn't assuage any of my concerns, and didn't help me see her side of the story. Instead, it just bummed me the hell out.

Roiphe begins her piece by describing all the women who were afraid to go on record for her piece—women who, allegedly, have grave concerns about the current #metoo movement. They're scared of the backlash from "angry Twitter feminists,” the type of women Roiphe brazenly compares to Trump supporters, suggesting that the language they use on Twitter is akin to the Trumpian inclination to blame #allmuslims or #allimmigrants for almost any problem America may have. Roiphe, and the many anonymous women featured in her piece, are all ostensibly concerned about the well-being of men who are now desperately afraid to exist in any capacity that could be remotely misconstrued as sexual assault.

In preparing her essay, Roiphe delved into a piece Donegan wrote about how she had experienced the Trump election and some harsh realities she had to face while even her left-leaning male friends took the win in stride and her female friends clutched each other and cried. Detailing her own response to Trump’s win, Donegan describes finding a penis-shaped shot glass in her kitchen the next morning and throwing it against the wall. Roiphe explains, “Can you see why some of us are whispering? It is the sense of viciousness lying in wait, of violent hate just waiting to be unfurled, that leads people to keep their opinions to themselves, or to share them only with close friends.”

Roiphe’s attempt to characterize Donegan’s anger at a shot glass as “violent hate” is exactly the kind of angry-feminist narrative bullshit that has flagged women for decades. Women are not allowed, and have never been allowed, to express anger or disdain without it being seen as hysterical. Public (or apparently even private) exclamations of anger are immediately dismissed as violent and irrational instead of being seen for what they are—a vocal expression from a large segment of the population that has routinely been the subject of abuse and is no longer taking that abuse with quiet tolerance. We're used to this sort of rhetoric from men, yet it's especially disheartening to have this kind of narrative perpetuated by one of us. I'm not suggesting we give any and all women passes to say anything they please, even if it's problematic (case in point: my issues with Katie Roiphe herself), but I take issue with a tired narrative of the bra-burning, man-hating, hysterical woman running around on her period hunting for men to devour.

Another troublesome point Roiphe makes in her piece involves a Joan Didion-inspired response to a Rebecca Solnit interview, wherein Solnit expresses the frightening reality of navigating the world as a female. Roiphe calls upon Didion's quote about the early ‘70s feminist movement. "Increasingly,” Roiphe quotes Didion, “it seemed that the aversion was to adult sexual life itself: how much cleaner to stay forever children." She continues:

“Didion’s phrase rang in my mind as I read Rebecca Solnit’s comment in the interview quoted earlier:

‘Every woman, every day, when she leaves her house, starts to think about safety. Can I go here? Should I go out there?. . . Do I need to find a taxi? Is the taxi driver going to rape me? You know, women are so hemmed in by fear of men, it profoundly limits our lives’

(To this, one of the deeply anonymous says, ‘I feel blessed to live in a society where you are free to walk through the city at night. I just don’t think those of us who are privileged white women with careers are really that afraid.’)”

Even if we take what this anonymous person said as true—that, as "privileged white women with careers,” we're not all that afraid of walking around at night—it's still a problematic to use this point to criticize the greater #metoo movement. White women are afraid to walk around at night. That is a fact. It is also true that white women are afforded exceedingly far more privileges than women of color. That is a fact, too. But just because some things don't affect white women as often or as deeply as women of color, does not mean white women should not fight this fight for and with women of color. If feminism is not intersectional, it's not feminism. Roiphe seems to tacitly suggest that since some of these fears are only experienced by women of a certain race or socio-economic class, that fear is somehow less relevant.

Using Didion's quote about our aversion to adult sexual life, too, while thought-provoking, doesn't really carry weight in today's America. As sexual adults, we don't want to remain children insofar as our views of sex go. But there's a difference between not having an active sexual life and refusing to tolerate the advances of men who have power over us. Women who don't want to be hit on by their bosses understand that getting hit on is not rape; women who don't want to be hit on by their bosses are also not asking to be treated like children. These two conditions are not mutually exclusive.

Roiphe ends her essay by waxing poetic about how she understands that the movement is enticing and exciting, maybe even an escape from our troubled and boring lives. Maybe this gives us all of us purpose, and isn't that nice? For me, however, Roiphe is the one seeking a purpose. Her essay comes across as a failed attempt at playing contemporary Joan Didion, daring to question the feminists of her time and relishing in how brave she is for doing so. I hope it does give her a sense of purpose. But in the words of one of her anonymous sources, "This seems like such a boring way to look at your life."