I’ve always believed in the school of thought saying timelessness of a song is relative to the frequency with which a that song is sampled. It’s probably my basis for spending shameful amounts of time foraging soul sample playlists, and also the reason I’m sometimes perplexed by an original artist’s refusal to clear his or her music. If a person is so moved by your work that it inspires them to create their own art, why not let your music see new light? Isn’t it a testament to the staying power and genius of the original work? David Bowie seems to have agreed with this sentiment. As did James Brown. But there is another, lesser-known entity who also doesn’t seem to mind a producer digging into her back catalog (as long she receives her rightful share), and it’s important that you know who she is. Do you know who she is? Because I’ll tell you who she is. She is Sister Nancy.

You’ve probably heard 1982’s Bam Bam by way of Belly, The Interview, or your roommate who likes weed a lot (but who also definitely found it through The Interview), but nevertheless, it is a classic. I’m certainly guilty of overplaying it around the house, and was more-than-thrilled when Kanye West and Swizz Beatz flipped it for the outro to Famous. (Which, wow: it's important that you know how smart the outro to Famous is.) (It takes a gifted producer to rework a piece of music into something new and popular.) (It takes Kanye West and Swizz Beatz to repitch and restructure a melody like Bam Bam’s to fit seamlessly and beautifully over a Nina Simone chord progression.) But perhaps the most relevant use of Sister Nancy’s dancehall banger comes via Jay-Z’s Bam—the second single off his Grammy-nominated 4:44 album—produced by No I.D.

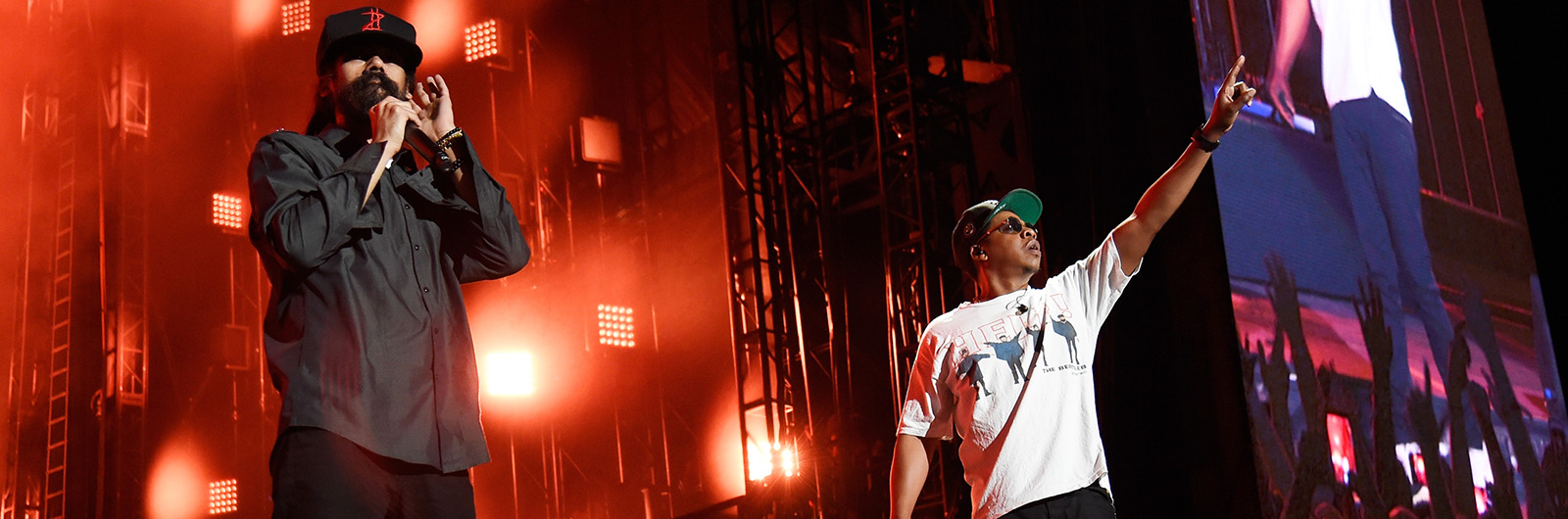

The music video is structured into a mini-documentary set in Trench Town, Jamaica, wherein Damian Marley—who is featured on the song’s hook—takes Jay on a tour of his father Bob’s old neighborhood. This is especially nice, seeing as it provides us with extra insight from the musician's perspective, like this neat tidbit from Jay-Z’s longtime engineer, Young Guru: “It’s influenced a lot of what we do. Our whole genre is birthed out of traditions out of Reggae… It’s the essence of us borrowing from our ancestors but recreating it and representing it.” There’s a reason they incorporated this soundbite into the video: it’s the very same blueprint No I.D.—a bona fide beat-legend—used to repackage Bam Bam into the icy cold canvas that Jay and Damian would later paint over.

It’s also the same approach Marley would use to craft the track’s hook, which you can hear 55 seconds into the music of Bam. It’s a sharp, demanding melody that can be traced back to the 15-second mark of Jacob Miller’s Tenement Yard:

Not so sharp and demanding, though, right? Tenement Yard, originally released in 1979, is perhaps more akin to your Saturday morning breakfast jam, yet Marley repurposes the lick to fit the darker, harder tone of Jay-Z—and he doesn’t stop there. Marley again reaches into the vinyl crates to flip Nicodemus and Junior Cat’s major (at 1:40, below) to Jay’s minor (at 4:59 of Bam, above):

Marley’s interpretation of the lyric is slightly different, which is essentially to say: don’t bother me when I’m enjoying a nice dance with a spliff and a Guinness (a perfectly reasonable request). To which of the aforementioned songs is he dancing, though? That’s for you to decide. I find they all suit Marley’s intentions—and the criteria of his ancestor’s—just fine.